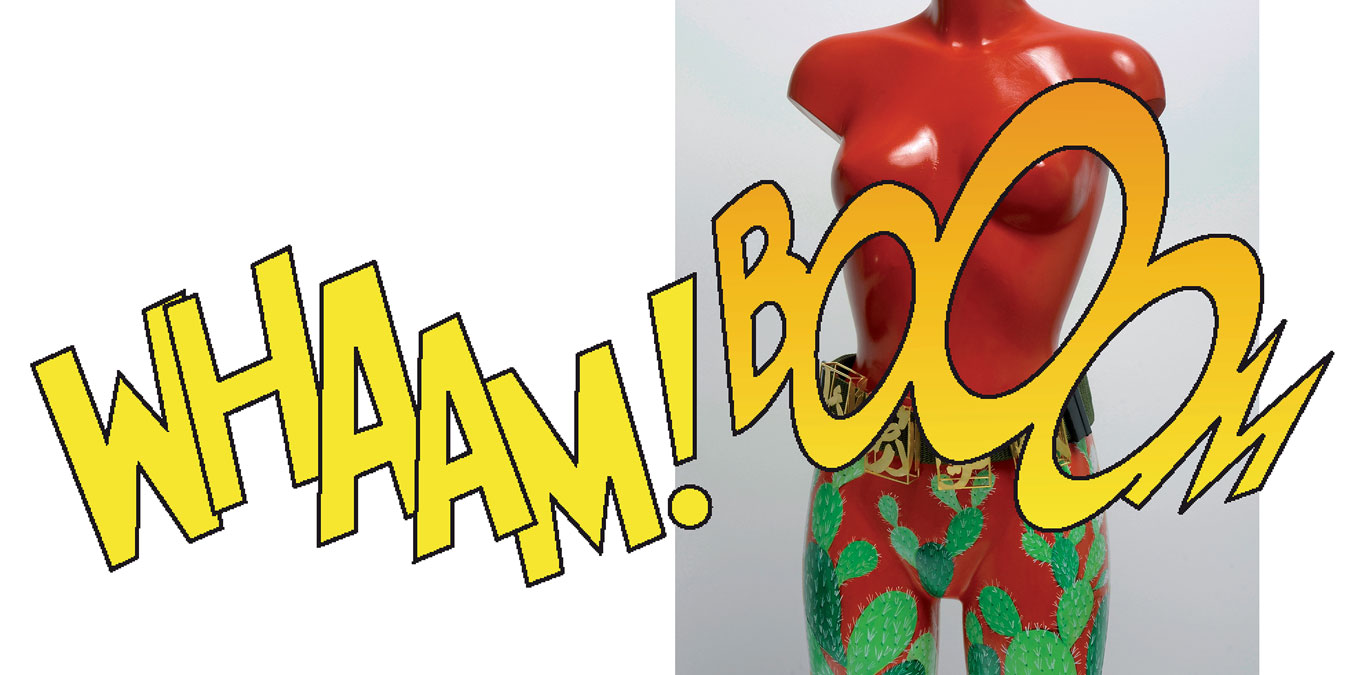

LAILA SHAWA: The Other Side of Paradise

CMYK.jpg)

Photography and mixed media on canvas,

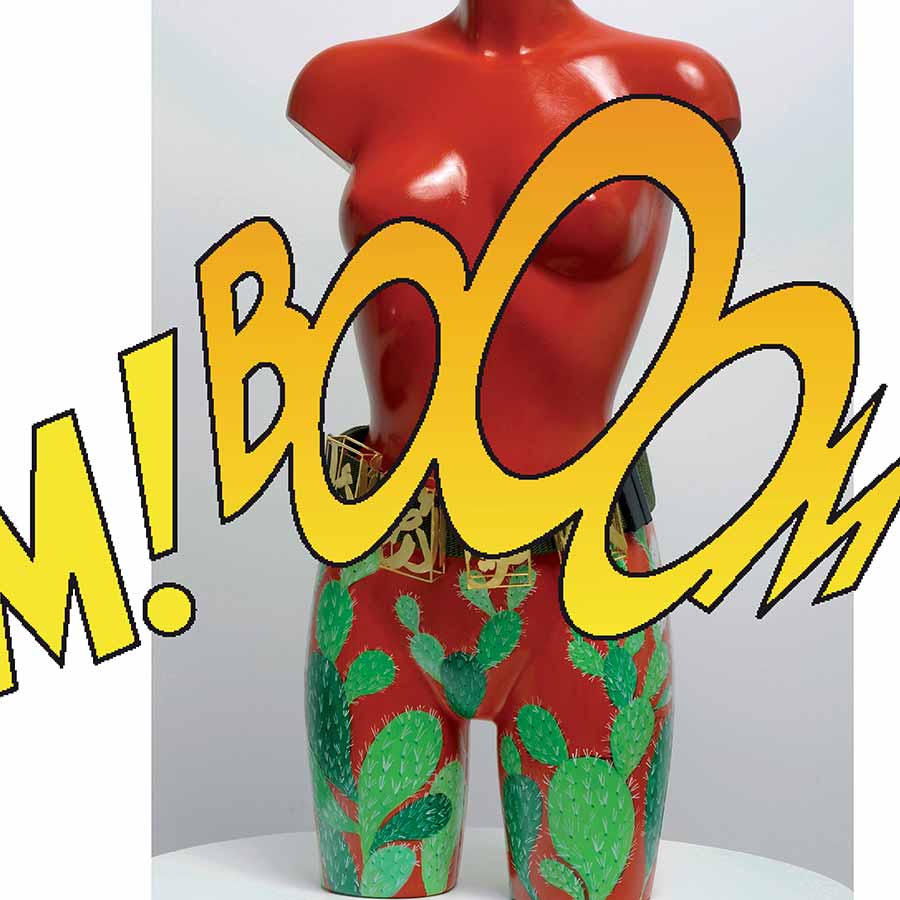

170 x 95 cm. Edition of 2.

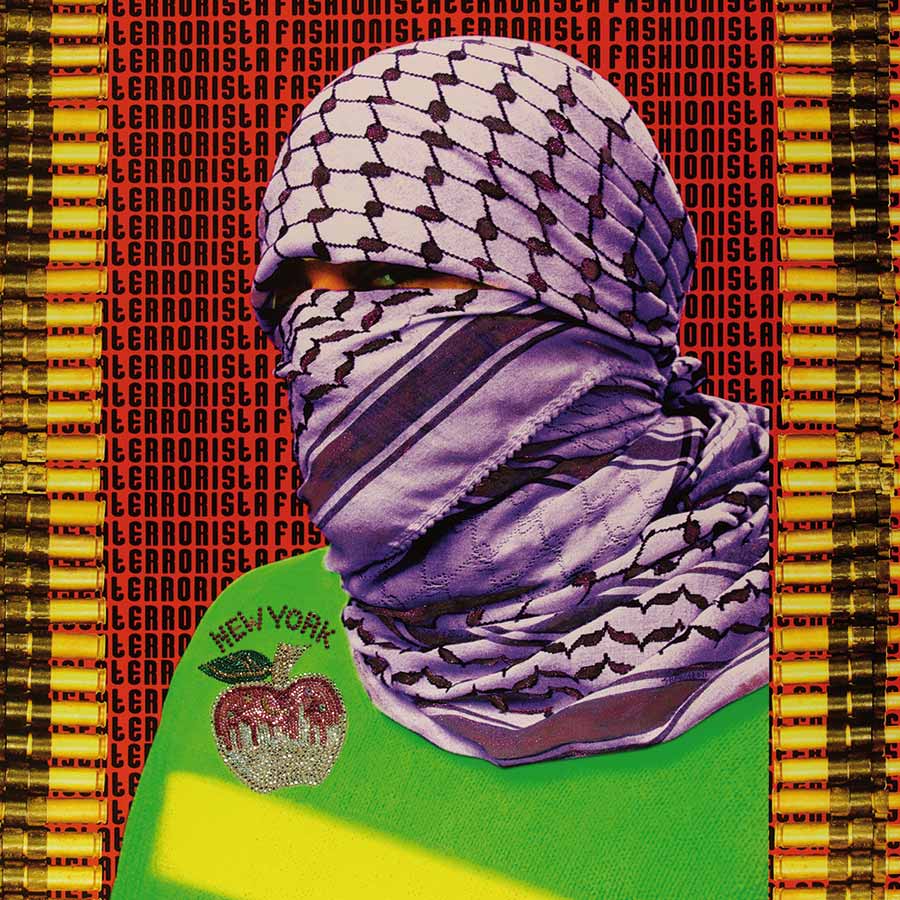

Mixed media on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

The October Gallery is proud to present the most recent canvases and sculptures created by Laila Shawa, an artist known for her uncompromising documentation of events in today’s Middle East. Laila Shawa was just eight years-old when, on May 14th, 1948, the State of Israel was declared to exist in her homeland of Palestine. Since then, her artistic career has developed in lock-step with the major episodes of modern Palestinian history, chronicling the trials and tragedies that are routinely obscured by the media, and lending a plangent voice to the silenced majority of Palestinians unable to speak out for themselves.

The contradictions of a logic spiralling beyond all rational control are a signature device in Shawa’s account of the current chaos in Palestine. The titles of these bright canvases, Trapped, Boom, and Cast Lead (the Israeli designation for the three-week long aerial bombardment and ground-invasion of Gaza, beginning in late December, 2008) attest to the inherent difficulties of art when tackling certain subjects head-on. The canvases juxtapose ironic references to Persian miniatures, fictional, comic-book characters, with a nod to Roy Lichtenstein’s Whaam, whilst depicting the deadly Predator drones endlessly circling in the skies above Gaza. These transform into Birds of Paradise, as Shawa searches for a solid point of purchase from which to express the insufferable, mounting pressure that rips the fabric of the real world to shreds.

This series of works developed from a Chanel 4 documentary, ‘The Cult of the Suicide Bomber’(2007), which aired CCTV footage of a young Palestinian woman caught crossing the border wearing a suicide belt. Trapped in a cage, and forced to undress, the harrowing film shows her mounting frustration and final despair at being unable to end the unbearable pressure by destroying herself, when the device she was carrying failed to detonate. Shawa uses freeze-frames from this awful footage, digitally combining them with imagery edited from cartoons, news footage and photographs of dolls who serve as mute puppets re-enacting the real-time political traumas of the present. These mixed media works see-saw between hyper-realism and surreal landscapes of the imagination; between stark representation and vivid interpretation; and between brutal distortion and fantasy-fuelled idealist aspiration. In the Trapped series, each silk-screened repetition of the woman’s anguished scream as she’s caught in the grip of total despair is overwritten with the barbed-wire scribble of illegible calligraphy – an Arabic form of greeking – which emphasises how belief, identity and perhaps even culture itself are rooted in systems of language riddled with miscomprehension and paradox.

Few artists choose to speculate about what motivates a woman to blow herself up in the service of a cause. Some depict them as fundamentalist fanatics, while to others they are traumatised victims of a male-dominated society, with little to mediate between these two polarised extremes. Shawa, in her tongue-in-cheek analysis of the complexities of this undeniably real career choice co-opts the coded language of fashion design, as her mannequins model various realisations of what might actually encourage a woman to destroy herself rather than live out a life she finds unbearable. One of the sculpted mannequin’s bodies is covered in roses, a reference to Arafat’s speech in Ramallah where he proclaimed ‘Women and men are equal!’ to a thousand women, before continuing, ‘You are my army of roses that will crush the Israeli tanks.’ Whilst Arafat seemed unaware of the irony of Palestinian women finally achieving their goal of sexual equality at such an unenviable price, Shawa, is not so naïve, and delicately fleshes out the deadly mechanism lurking at the heart of Arafat’s rhetorical flourish.

Shawa is little interested, perhaps, in providing ready-made answers to the myriad questions raised by the conflicting view-points she depicts. Instead, her work prompts us to ask ourselves the simpler questions: If I were in such a situation, how would I feel, and what would I do? Even if the works don’t offer any easy solutions – at least they clearly define some of the many serious questions just begging to be asked.